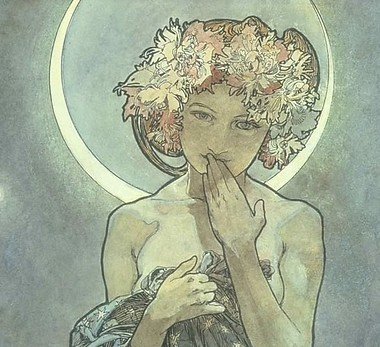

Dreams

as part of

the Creative Process

Each dream is practice in entering

the underworld, a preparation of the

psyche for death.

J. Hillman

Dream Interpretation &

the Creation of Symbolic Meaning

Rational thought and language uses linear thinking, so that clarity is achieved by following a defined sequence. Nondiscursive thought, on the other hand, involves network thinking, where all elements of the network are potentially present at once. Therefore the apprehension of the network requires thinking tools that act as network hubs, in which links in the network converge—in short, symbols. The more complex the network, that is the greater the number of associative hubs that are linked together in the overall structure, the greater the potential range of meanings—hence the idea of the dream, or the work of art, as a web of infinite possibilities.

Similarly, then, dream interpretation requires an attitude that is open and allusive, making links and raising possibilities rather than attempting to find a "solution," a "correct" interpretation that closes down the potential of the dream by reducing it to only one thing. Unlike scientific facts and theories, whose validity decreases to the extent that they are ambiguous or susceptible to multiple interpretations, the value of symbols and their interpretation increases according to how multiple and indeterminate are the interpretations of which they are capable. This is the rational for the "negative capability" recommended by Keats for poets and adopted by Bion as a recommendation for psychoanalysts. Negative capability, the capacity for "being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason" (Keats) is the requisite state of mind for both the production of symbolic images (the dreamer, the poet) and their interpretation (the psychoanalyst).

The dreaming mind produces metaphors, images and symbols "naturally" spontaneously, in the same negative way indicated by Keats: it is because of what the mind is not doing (reaching after fact and reason) that it is able to produce the the multiple meanings of the dream. The poet and the analyst cultivate this mental faculty in order to, as it were, learn to speak—and interpret—the “natural” unconscious language of the dream. In both cases, it requires the development of a state of mind that partakes of both waking and sleeping forms of thinking, suppressing cognitive functions sufficiently to allow a dream-like state to develop while maintaining them enough to be able to attribute metaphorical and symbolic meaning to the “dream-thoughts” that emerge. Bion called this the analyst’s “reverie”; Jung called it the transcendent function.

If dreaming is a form of nondiscursive symbolism, this would suggest that dreaming, or perhaps more broadly unconscious imagining, is the raw material not only for art but for any creative activity that utilizes symbolic imagination as a way of reflecting on the emotional and spiritual aspects of our psychic life—that is, our subjective experience. Art, religion and psychoanalysis all provide imaginative arenas that foster the conscious development of imaginal capacity through the elaboration of symbolic imagery. In this way, they might be seen as a consciously cultivated form of dreaming.

W. Coleman

The Advantages of Jung’s Theory

Dreams have been described as the 'dress rehearsal' for life. As this implies, they cover much varied ground, trying out many possibilities that the future could hold in store, before the flesh-and-blood live performance is acted out once and for all.

Their scope (in the realm of the potential) is enormous: they are far too free and extravagant to be fitted into any kind of mold, but they do all arise from the most primitive part of the mind and are determined more by the strength of the emotions within than by any other consideration. It is this primitive and emotional content that is their essential value. Through them the individual can make contact with the roots of his being and his own true needs.

In a crisis, when his life is particularly threatened by outside circumstances or inner stultification, a person usually has his most vivid and meaningful dreams, and these will be all the more effective if he pays attention to them and respects them.

Dreams are also disconcertingly honest, so that unless the individual is prepared to be completely sincere, it is a waste of time to unearth their hidden meaning, only to reject it out of hand.

T. Chetwynd